CATHY HARVEY & REBECCA ALLAN

Clinical history:

Buddy, a 4-year-old neutered male Border Collie presented with lethargy and an in-house PCV of 12%. There was no free blood in the abdomen and the spleen was normal. He had progressive pancytopenia without regeneration, a single dose of dexamethasone and two blood transfusions, before bone marrow samples and blood smears were submitted to the laboratory.

Haematology findings:

In the peripheral blood smears, platelets were clumped but appeared decreased, with occasional large and atypical shaped platelets. There were rare cells containing fine cytoplasmic eosinophilic granules, which may be megakaryocyte/blast in origin. Erythrocytes appeared normal morphologically.

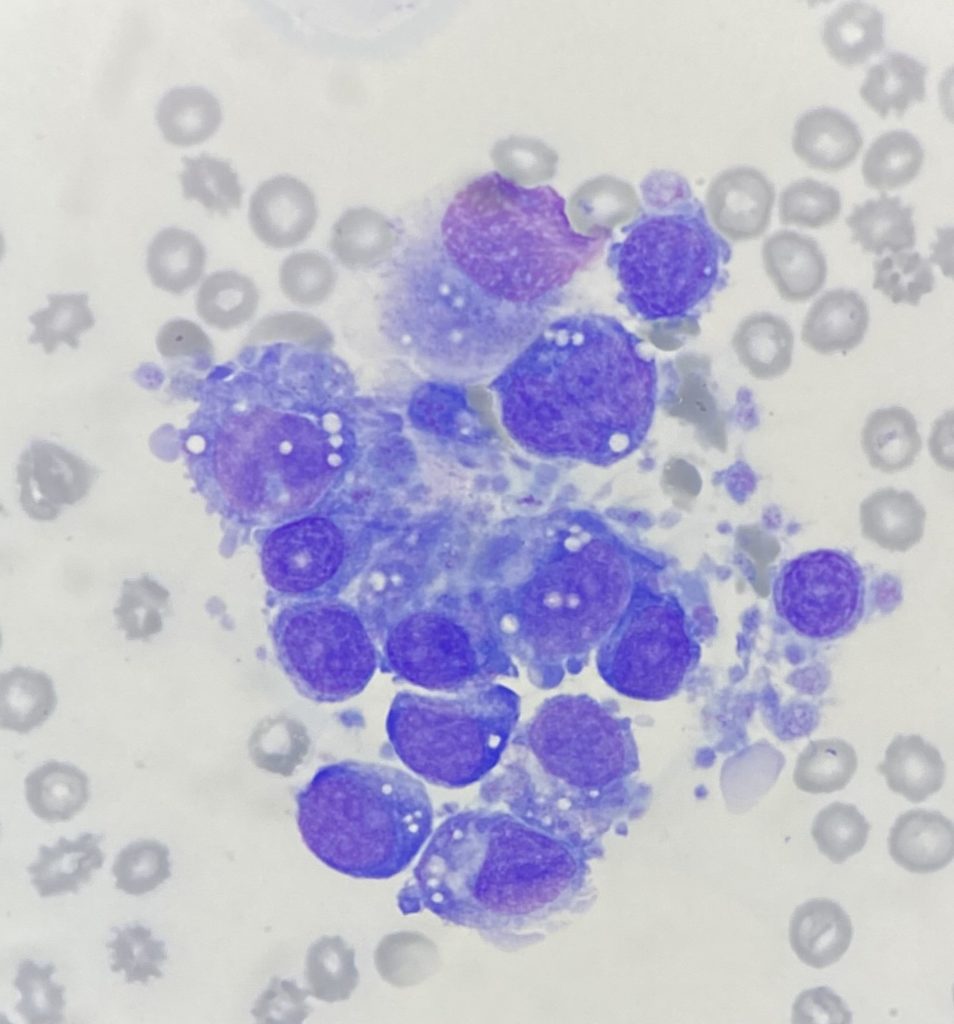

Bone marrow cytology:

The seven smears had low to moderate cellularity and consisted of variably sized aggregates of cells. A 100-cell differential consisted of 8% erythroid cells, 15% myeloid cells and 77% atypical cells, plus low numbers of plasma cells, macrophages and lymphocytes. The atypical cells had a pleomorphic appearance with round to oval nuclei, variably prominent nucleoli and low to moderate amounts of basophilic cytoplasm, variably containing small vacuoles and fine eosinophilic granules, frequently with peripheral cytoplasmic blebs that have the appearance of platelets. These cells were surrounded by platelets, some of which were large and atypical in morphology. Binucleate cells, rare small multinucleated cells, mitotic figures and erythrophagocytic cells were noted in low numbers. Both myeloid and erythroid cells were too few to assess.

These findings suggested proliferation of pleomorphic cells with features suspicious of megakaryocytic origin.

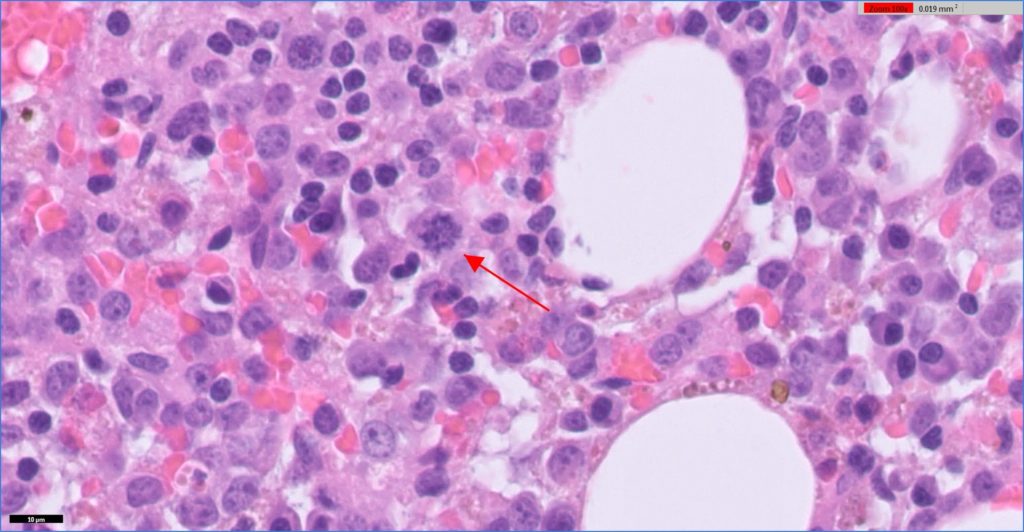

Bone marrow histopathology:

The samples consisted of blood with scattered islands of adipocytes and haematopoietic tissue. The haematopoietic tissue was cellular but lacked trabeculae. The majority of cells consisted of immature round cells with moderate anisokaryosis, multiple small nucleoli and a small amount of eosinophilic material. Some of the cells had multiple nuclei. There were mitotic figures readily evident. There were rare mature granulocytic cells and no normal mature megakaryocytes. The erythroid line seemed complete, but erythropoiesis appeared reduced.

Histopathology indicated myeloid leukaemia (probably megakaryocyte origin) with hypoplasia or ineffective haematopoiesis of all lines.

Diagnosis:

The large numbers of atypical cells with features consistent of megakaryocytic origin are strongly suggestive of megakaryoblastic leukaemia (acute myeloid leukaemia, AML with megakaryoblastic differentiation); however, other myeloid cell lines couldn’t be excluded.

Discussion:

This case was the subject of extensive discussion by anatomic and clinical pathologists throughout our network of laboratories. The cytology and histopathology preparations (slides examined microscopically and also on digital platforms) as well as digital images were examined collaboratively across the Gribbles’ pathologist “hive-mind” in multiple geographic sites and multiple disciplines.

Myeloid neoplasms in animals are relatively uncommon, but probably also under diagnosed, because biopsies and bone marrow aspirates submitted to diagnostic laboratories are often of insufficient quality to establish a diagnosis. It is difficult to make a diagnosis from a single snapshot of even a good quality bone marrow biopsy. AML in some instances may be fatal before a bone marrow biopsy has been collected, and animals are not consistently submitted for post-mortem examination.

Myeloid neoplasia should be suspected if an animal has persistent anaemia, thrombocytopenia, or neutropenia without obvious cause such as blood loss, inflammation, or immune mediated destruction of blood cells. The clinician, clinical pathologist and anatomic pathologist have to carefully integrate a thorough history, the haematology results and bone marrow findings to derive a possible diagnosis of myeloid neoplasia.

In order to fully assess the bone marrow both cytological and histological evaluation is necessary. The strength of cytology

evaluation of aspirates is the qualitative assessment of cell features (granulation, vacuolation, haemoglobinization, dysplasia, stain intensity and chromatin patterns), while histology evaluation is essential to quantitatively evaluate overall cellularity, topography, mitotic rate, bony trabeculae and stroma. Identification of cell type is best accomplished by cytology. Histopathology is used to assess overall composition of the marrow and other haemolymphatic organs, but identification of cells is more difficult.

Steps to establish a diagnosis of myeloid neoplasia:

1. Rule out lymphoid neoplasia

2. Complete blood cell count

3. Review of the blood film

4. Aspirate bone marrow for cytology

5. Biopsy bone marrow for histopathology

6. Flow cytometry (currently not available in NZ at this time), or immunophenotyping (only lymphoid markers available in NZ)

The diagnosis is based on:

> Presence and persistence of cytopenia and or persistent increase in one cell type.

> Identification of increased blasts cells in the blood and/or bone marrow and/or myelopthisis and/or dysplasia.

> Subcategorization using immunoassays such as flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry can also be used if available.

AML (acute myeloid leukemia) is defined as cytopenia and > 20% blast cells in the blood or bone marrow. AML most often results from acquired genetic lesions in stem cells. All ages of animals can be affected, but larger surveys indicate that AML is most common in young to middle-aged animals. Large breed dogs may be over represented, in particular German Shepherd dogs. Clinical presentation consists of non-specific illness over days to weeks with ecchymosis due to lack of platelets, exercise intolerance due to anaemia, or fever due to neutropenia. AML is an aggressive neoplasm, generally causing grave illness, poor quality of life and leading to death. However, a multiagent intensive chemotherapy protocol has yielded approximately 2-year survival and quality of life and one dog with AML, and in another study some dogs have survived for greater than a year with single agent chemotherapy suggesting outcomes may not be uniformly fatal.

Buddy is still doing well and is continuing to go to his owner’s bach in Franz Josef for weekends.

Many thanks to Rangiora Vet Centre and West Coast Vets Ltd Hokitika for submitting excellent history and samples from this challenging case.

Reference: Tumors of the Hemolymphatic System. Myeloid Neoplasms. In: Donald J. Meuten (eds). Tumors in Domestic Animals 5th Edtn. Pp 288-305. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017.